Authorities in the eastern province of Shandong have detained a Hui Muslim poet and author after he tweeted about the incarceration, surveillance and persecution of Chinese Muslims, both in Xinjiang and across China, RFA has learned.

Poet Cui Haoxin—known by his pen name An Ran—was detained by state security police in the provincial capital Jinan on Friday, when families traditionally gather to mark the Lunar New Year.

Cui is currently being held under criminal detention on suspicion of “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble,” a charge frequently leveled at peaceful critics of the ruling Chinese Communist Party.

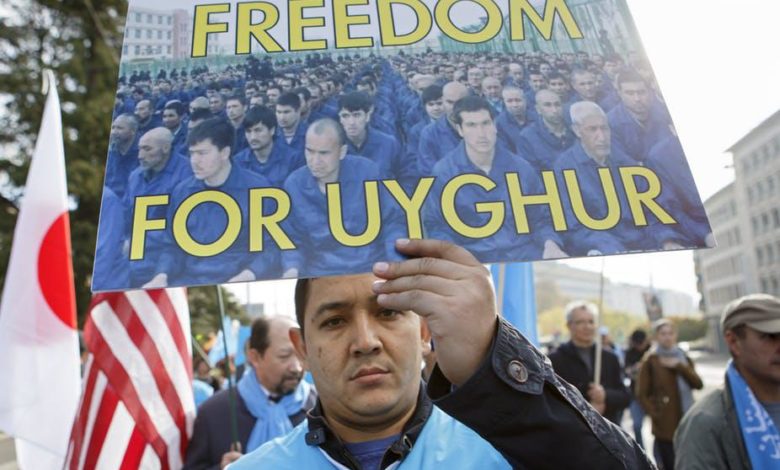

It was unclear what had triggered his detention, but Cui has been an outspoken critic of China’s mass incarceration of Uyghurs and other Muslims in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, where authorities have placed as many as 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities accused of harboring “strong religious views” and “politically incorrect” ideas in a network of internment camps since April 2017.

While Beijing initially denied the existence of the camps, Chinese officials have more recently begun describing the facilities as “boarding schools” that provide vocational training for Uyghurs, discourage “radicalization,” and help protect the country from terrorism.

But reporting by RFA’s Uyghur Service and other media outlets indicate that those in the camps are detained against their will and subjected to political indoctrination, routinely face rough treatment at the hands of their overseers, and endure poor diets and unhygienic conditions in the often overcrowded facilities.

RFA has confirmed dozens of cases of deaths in detention or shortly after release since the internment system began, and while only a handful can be definitively linked to torture or abuse, several appear to be the result of “willful negligence” by authorities who do not provide access to sufficient treatment or of poor camp conditions that exacerbate an existing medical condition.

Woman’s story told

Cui posted to his Twitter account on Jan. 12 about his reaction to the story of a Hui Muslim woman who was locked up in a “re-education camp” as she vacationed back in China from studying in the United States, her degree still incomplete.

“There are about one million Hui Muslims in #Xinjiang,” Cui wrote in a series of tweets after reading her story, adding that he had narrowly avoided being sent for “re-education” himself in 2018.

“I was also requested to receive an additional check like that Hui girl in story, but I refused,” Cui wrote. “That [was] outside JingGangShan airport on 8 April 2018.”

He also referred to the experience of a Hui Muslim friend in Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture in the western province of Gansu, who was told to delete a video from WeChat of the large-scale demolition of local mosques.

“There are several hundred mosques and facing the destruction on the large scale. One day, he sadly saw the scene and shot it. After he share the video on Wechat, he soon received the call of political police,” Cui tweeted.

He added: “[The] Xinjiang model is not a distant rumor. Muslim minorities live in the surveillance and fear.”

Cui was detained and questioned by state security police in 2018 over critical tweets, and warned not to use overseas social media or to become a “tool” of hostile foreign forces.

In April 2018, Cui was sent on a weeklong ‘re-education course’ in eastern China and was briefly detained in connection with his poetry and other writings that reference Xinjiang, it said.

Jailed for 11 months

The Washington Post reported recently on the case of Hui university student Zhou Yueming, also known as Vera Zhou, who was incarcerated by authorities in Kuitun, Xinjiang, after she returned home to visit her father and submitted a college assignment using a banned VPN service to circumvent China’s Great Firewall of internet blocks and filters.

Zhou, 21, spent 11 months in a small cell with 11 other Muslim women with no trial or charges brought against her. She was denied proper medical treatment despite being a cancer patient.

Inside the camp, prisoners were forced to sing revolutionary songs, and were banned from speaking any language other than Chinese. They were also prevented from practising their religion.

Following Zhou’s release, the Kuitun authorities confiscated her passport and kept her under surveillance for a further 18 months before finally allowing her to resume her studies in the United States.

Her mother Ma Caiyun told RFA that her daughter has been traumatized by her ordeal and that the family has hired a lawyer in the U.S. to represent her interests.

“She has been very damaged by this thing that happened all of a sudden, as you can imagine,” Ma said. “She is seeing a psychologist.”

School fails to help

Bob Fu, founder and president of the Christian rights group ChinaAid said Zhou had been released to continue her studies after diplomatic pressure from Washington, but that she had been forced to sign a gag order before she could get her passport back.

“This shows the kind of religious persecution the Chinese Communist Party engages in a regime with no rule of law,” Fu told RFA. He hit out at Zhou’s school, the University of Washington, for failing to call for her release when it knew very well what had befallen her.

“It is shameless and chilling that they refused to make any representations to the Chinese government,” Fu said. “It looks as if the University of Washington kowtowed to China to preserve its exchanges with them.”

The school currently has an exchange program with Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University and a Confucius Institute, run by the State Council’s language teaching and cultural exchange office the Hanban, on campus.

Zhou may be free, but her ordeal is far from over.

The University of Washington has continued to bill her for tuition fees, and she is in default on her student loans since being incarcerated.

A group of alumni appealed to the president of the university on Jan. 10 to throw Zhou a financial lifeline and to make public statements supporting her.

The school has said there is little it can do, as Zhou is a Chinese national.

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) has said it is “deeply concerned” by reports that China “has turned the [Xinjiang] Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) into something that resembles a massive internment camp that is shrouded in secrecy” in the name of eradicating “religious extremism” and “maintaining social stability.”